Principles of defense

The most important principle of defense in the Noble and Worthy Science is the principle of single-time defense, meaning that the defender should parry and counter-attack simultaneously. Essentially all rapier masters advocate single-time attacks, but Swetnam’s interpretation of this term is unusual. When other authors refer to single time responses, they are referring to a single movement of the sword alone which simultaneously parries the incoming attack and injures the opponent. When Swetnam uses the term, he is almost always talking about a parry with the dagger accompanied by a simultaneous attack with the sword. Offensively, the same rule applies, the sword makes the attack while the dagger moves simultaneously to protect.

“To take time, that is to say when opportunity is proffered thee, wither by his lying unregarded or upon thy enemies proffer, then make a quicke answer, I meane it must be done upon the very motion of his proffer, thou must defend and seeke to offend all at once…” (p. 83)

“…thou must consume no time in staying anie space betwixt thy Defence and Offence, for thou must not make two times of that which may be done at one time…” (p. 98)

“…for if you will hit your enemie, your offence and defence must be done all with one motion, whereas if you continue a space betwixt your defence and your offence, then is your best time of offence spent, for when your enemie chargeth you, either with blow or thrust, at that verie instant time, his face, his rapier, arme, shoulder, knee, and legge are all discovered, and lie open…” (p. 90)

Secondly, Swetnam advises the fencer to maintain a good distance and to defend that distance fiercely. Unlike most other rapier masters, Swetnam does not use stringering (stringere) to constrain the opponent’s blade as they enter into measure. Instead, he attacks, forcing the opponent to respond and then using that response to create an opening.

”…if hee doe breake distance by anie of those waies, although hee doe it never so actively, yet may you defend your selfe with your Dagger and either offend your enemie with a suddaine falling of the point, and with the same motion chop in with a thrust to that part which liest most discovered as you may quickly perceive when you see his lying.” (p. 94)

“and if thine enemie doe incroach within thy distance, then be doing with him betimes in the verie instant of his motion whether it be motion of his body, or the motion of his weapon, or in the motion of both together; put out thy point, but not too farre, but as thou maiest have thy rapier under command for thy owne defence, and also to provide him ready againe to make a full thrust home, in the instant of thy enemies assault” (p. 95)

Next, every attack is parried. Swetnam never defends any attack with a step or body void alone, and never ignores a potential attack as a feint. This is an unusual attitude in a fencing master who uses feints in almost every attack, but it makes sense in context. Swetnam’s feints, like all feints, are intended to draw overlarge responses from one’s opponent and thereby create openings in the opponent’s defense. This explains his insistence on intertwining the concepts that each attack must be parried, but each parry must be as small as possible.

“You must be very carefull that you doe not overcarry your Rapier in the defence in anie maner of thrust, yet you must carrie him a little against every proffer which your enemie doth make: for if a man be verie skilfull, yet is he not certaine when his enemie doth charge his point upon him, and proffer a thrust, whether that thrust will come home, or no: wherefor (as I said) you must beare your Rapier against everie thrust to defend it, but beare him but halfe a foote towards the left side, for that will cleare the bodie from danger of his thrust, and so quicke backe againe in his place, whereby to meete his weapon on the other side, if he charge you with a second thrust, thinking to deceive you as aforesaid.” (p. 120)

“…for there is no man so cunning, that kneweth if a thrust be proffered within distance, but that I may hit him, or whether it will be a false thrust, or no, the defender knowes not, and therefore he must prepare his defence against every thrust, that is proffered.” (p. 123)

He does advocate letting cuts “slip” past without parrying, retracting the rapier and sometimes stepping back with the front foot, followed by an attack after the cut has gone past. While the blow isn’t parried, the rapier is held almost vertically during this void. If the cut happens to reach further than the defender anticipates, the vertical blade will provide a last ditch defense for the entire body. This concept of allowing blows to pass before counter-attacking is very similar to some techniques in Silver’s Brief Instructions and quite different from contemporary rapier masters.

Fourth, thrusts should be parried with the dagger alone whenever possible. Dagger parries are quicker than rapier parries, and this frees up the rapier for the simultaneous counter-attack and to catch any potential disengage around the dagger parry. Particularly hard thrusts can be parried with both weapons together, in the same manner as blows are parried.

“the best way is in lying in your guard according to the first picture, as your enemie commeth in with his passe suddenly upon the first motion, fall your point, and in the very same time put him out withall, and with your Dagger onely defend his passage”

Fifth, as the dagger moves to parry the sword should move to the same side. For example, if the attacker makes a low thrust towards the left side of the belly, the defender should drop their dagger to sweep the thrust clear of their left side and simultaneously move their rapier forward with the knuckles of the rapier-hand pointing towards their left side, making a thrust at the attacker’s right shoulder. This neatly pre-positions the rapier to catch any potential disengage around the dagger, and is very difficult for the attacker to parry with their dagger.

(Click on the image to see the technique in motion)

“Therefore, if you doe make a false thrust, present it without the circle or compasse of his Dagger, that in his defence he may misse the hitting of your point, then hath hee but the single Rapier to defend your second thrust, and he must make his preparation first before hand with his Rapier, if such an occasion be offered, otherwise it cannot be defended.” (p. 104)

Techniques of defense

Swetnam divides defense into two categories, thrusts and blows. Thrusts are most often defended by the dagger alone, but blows are best defended by a simultaneous parry with both weapons.

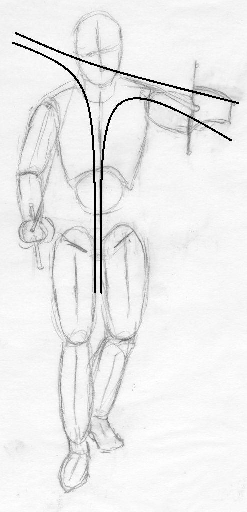

When standing in a True Guard, the body is divided into several zones, each of which has a pre-set parry and riposte.

The zones are:

- Below the dagger, left of the center line

- Below the dagger, right of the center line

- Above the dagger.

Figure 7. Defensive zones for parries

All of these defensive zones are dagger-centric, not rapier-centric. The ideal response to any attack is a parry with the dagger and a simultaneous attack with the rapier, therefore it is better to think of the body in terms of dagger-parry zones. This can be a difficult mindset for fencers with ingrained habits from other rapier styles to learn, but the end result is faster dagger parries and safer counter-attacks.

Here are the stock responses to a thrust to each zone:

- Attacks below the dagger on the left side are parried by dropping the dagger point and sweeping the thrust clear of the left side. The accompanying counterattack should be made to the right shoulder or chest, with the rapier knuckles pointed inwards.

“…when you breake a thrust, turne but your hand-wrist about, letting fall the point of your Dagger downe-ward, but keepe out your Dagger-arme so stiffe as you can, so shall you bee readie to defend twentie thrusts one after another, if they come never so thicke, and likewise you are as readie for a blow…” (p. 116)

(Click on the image to see the technique in motion)

- Attacks below the dagger on the right side are parried by dropping the dagger hilt, and then parrying down and across the body to the right with the dagger held vertically. The accompanying counterattack should be an Imbrokata to the left shoulder or face. This parry is somewhat slow, so if the incoming attack is very fast or powerful enough to blow through an incomplete parry, it can be necessary to slip back with the right foot to provide additional defensive depth.

“Now the second defence is with the dagger likewise, but then you must beare the hilt of your dagger so lowe as your girdle-steed, and the point more upright than is described in the first picture, and your defence of a thrust, you must beare your dagger hand stille over your bodie, without letting fall the point but still keeping him upright.” (p. 91)

(Click on the image to see the technique in motion)

- Attacks above the dagger are parried by placing the dagger blade under the incoming blade and raising. It is not necessary to move the dagger very much, because the dagger should already be held at eye level. The accompanying counterattack should be a lunge in quarte to the right side of the chest or belly, which has the added advantage of lowering the defender’s head below the attacker’s shot.

“…clap thy Dagger under his Rapier crosse-waies, and so bearing up his point over thy head, and at the verie same instant that thou ioynest with his Rapier, then chop in with thy Rapier point withall to offend him…”

(Click on the image to see the technique in motion)

For all these parries, it is best to maintain a wide measure from the opponent during the parry, even if this means stepping backwards. At distances closer than wide measure, it becomes increasingly easy for the opponent to angle their attack around the dagger parry.

Defending a cut

Cuts to the left side of the head should be defended by raising both weapons at about a 45 degree angle with the blades parallel to each other and catching the opponent’s blade with both weapons simultaneously.

“Now your bodie and weapons being thus placed as aforesaid, if your enemie strike a blow at you, either with sword or rapier, beare your rapier against the blow, so well as your dagger according to the rule of the Backe-sword, for in taking the blow double you shall the more surely defend your head”

Cuts to the left side of the body or to the left leg are defended by dropping the points of both weapons to a 45 degree angle with the blades parallel and catching the cut on both blades simultaneously.

“The fourth way is to defend a thrust with both your weapons together, and that you may doe three manner of waies, either with the points of both your weapons upwards, or both downward, upward you may frame your selfe into two guards, the first is according to as I have described before, the points being close together according to the picture, so carrie them both away together against your enemies thrust breaking towards your left side”

Cuts to the right of the center line are parried by bringing the dagger back slightly and bracing it against the back of the rapier in about the middle of the blade. The rapier blade should rest at the junction of the dagger blade and dagger quillon. This turns the entire rapier blade into a wall that can protect the right side. Once the blow is parried, the joined weapons can be used to push down the attacker’s weapon and the rapier can thrust out while still braced by the dagger, in a manner similar to a pool cue.

“the other high guard is to put your rapier on the out-side of your dagger, and with your dagger make a crosse, as it were, by ioyning him in the middest of your rapier, so high as your breast, and your dagger hilt in his usual place, and to defend the thrust, turne down the point of your rapier suddenly, and force him downe with your dagger, by letting them fall both together…”

These double parries are one of the keys to using a rapier and dagger against other weapons such as backsword and polearms. They allow the fencer to compensate for the relative lack of leverage inherent in a long one-handed weapon like the rapier.

“and this way defendeth the thrust of a staffe, having onlie a rapier and dagger, as you shall heare more when I come to the staffe: for it is good to be provided with the best way, if suddenly occasion be offered: and so for the blow of a staffe, you may verie easily defend with a Rapier and Dagger, by bearing him double”

The two left side double parries can be done as single time attacks, where the defender’s rapier and dagger parry the cut and, in the same motion, the defender’s rapier strikes the attacker. This is the one case where Swetnam uses the idea of attack and defense in one motion in the same manner as his Italian contemporaries.

“For the defence of a blow double, is sure, and yet you may answer your enemie so soone, and with as much danger to him as if you did defend it single, for it may all be done with one motion, both the defence and offence” (p. 50)

These double parries can also be used against thrusts from a rapier, but they are generally slower than single parries with the dagger and do not allow for a simultaneous counter-attack. It is best to use them only against extremely strong thrusts which might bull through a simple dagger parry. Swetnam mentions that the right side method, where the dagger reinforces the rapier, can be used to “defend a thrust before it come within three foot of your bodie”, basically making it possible to parry with the foible of one’s rapier, but I have found this tactic to be fairly risky as it limits my rapier’s range of motion before the opponent has really committed himself.

An almost identical set of double parries can be found in George Silver’s unpublished work, Brief Instructions Upon My Paradoxes of Defense. The following is Silver’s description of the right side double parry where the dagger reinforces the sword blade:

“If with his long sword or rapier he charges you aloft out of his open or true guardant fight, striking at the right side of your head, if you have a gauntlet or closed hilt upon your dagger hand, then ward it double with forehand ward, bearing your sword hilt to ward your right shoulder, with your knuckles upward & your sword point to ward the right side of his breast or shoulder, crossing your dagger on your sword blade” (Brief Instructions)

Another similar double parry can be also be found in Joachim Meyer’s 1570 German fencing manual:

“… at the same time as you parry with your dagger, go up with your weapon under his blade to help your dagger, so that you parry with both weapons at the same time.”

Countering disengages

Swetnam makes extensive use of feints and disengages to draw the opponent’s blade offline before committing to a real attack. It’s therefore unsurprising that he also describes a technique for dealing with a feint and subsequent disengage. Essentially, whenever one parries with the dagger the rapier should move towards the same side of the body in preparation to either catch the attacker’s blade as it disengages.

“but now the onely way to defend a false thrust, is with the single Rapier, for when that the Dagger falleth to cleare the fained thrust from the body, then the Rapier must save the upper part, I meane the face and shoulder, by bearing him over your bodie as you doe at the single Rapier, and so by that meanes the Rapier will defend all the bodie so low as your knee.”

If the defender does not pre-position the rapier as the dagger leaves its guard position but instead waits until the opponent disengages, it will be too late to parry with the rapier.

“Therefore, if you doe make a false thrust, present it without the circle or compasse of his Dagger, that in his defence he may misse the hitting of your point, then hath hee but the single Rapier to defend your second thrust, and he must make his preparation first before hand with his Rapier, if such an occasion be offered, otherwise it cannot be defended.” (p. 104)

Slips

When pressed by a strong attack, Swetnam recommends falling back a single step to allow the attack to fall short. The footwork for this technique is the same for both thrusts and cuts, but the bladework is different. Against a thrust, the attacker’s extended blade is then captured with the defender’s dagger and the right foot comes forward with the defender’s counter.

“…by an active and nimble shift of the body by falling back with the right foote, & the danger being past to change hastily upon your enemy again” (p. 100)

“A reverse is to be make, when your enemie by gathering in upon you, causeth you to fall backe with your right foote, and then your left foote being foremost, keeping up your dagger to defend, and having once broken your enemies thrust with your dagger, presently come in again with your right foote, and hand together, and so put in your reverse unto what part you please, for it will come with such force that it is hard to be prevented.” (p. 114)

Against a cut, as the right foot comes back, the defender’s rapier draws up vertically to serve as a last ditch defense in case the cut reaches the defender. Once the cut goes past, the defender counterattacks with their rapier, using their dagger to keep the attacker’s blade offline.

“Now if your enemy doe charge you with a blow, when as you see the blow comming, plucke in your Rapier, and let the blow slippe, and then answer him againe with a thrust, but bee carefull to plucke in your rapier to that cheeke which hee chargeth you at, so that if the blow doe reach home, you may defend him according unto the rule of the backsword.”

This second technique is once again very similar to one described by George Silver.